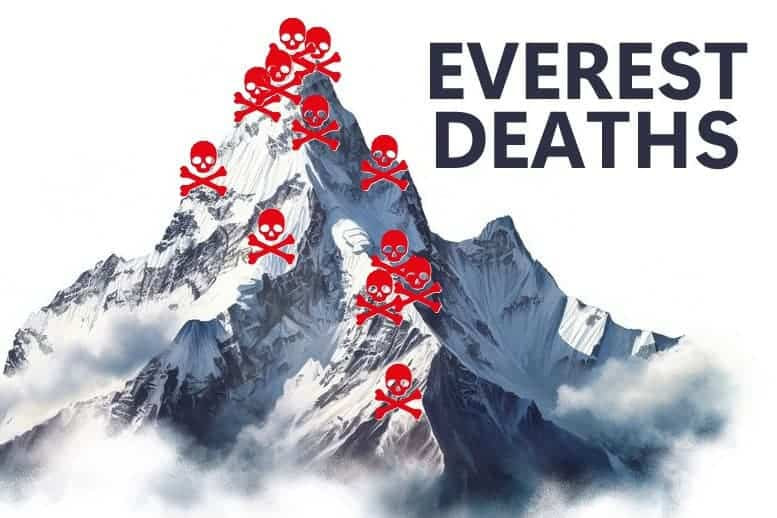

Mount Everest has long been a symbol of human aspiration and adventure. As the highest peak in the world at 29,032 feet (8,849 meters), the mountain comes with significant risks.

How Many People Die on Everest Each Year?

Since the first successful summit by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953, thousands of climbers have attempted to reach Everest’s peak, about 800 people anually. Between 2000 and 2019, the average number of Everest deaths was approximately 3.2 deaths per year. However, 2023 was the mountain’s deadliest year on record, with 17 deaths.

According to the Himalayan Database, over 340 people have died on Everest in total. More than 200 bodies still remain on the mountain. Bodies are left on Everest due to the difficulty, cost and risk involved in removing them.

What Makes Climbing Everest Dangerous?

Climbing Mount Everest is an incredibly challenging due to a combination of extreme altitude, harsh weather conditions, and difficult terrain. Even with the best equipment and support, these factors make Everest one of the most difficult and dangerous mountains to climb.

The altitude alone, with its thin air and low oxygen levels, imposes severe physiological stress on the body, often leading to potentally fatal altitude sickness. Additionally, the weather on Everest is notoriously unpredictable, bringing high winds, blizzards, and severe cold. Finally, the terrain features steep icefalls, deadly rock faces and crevasses that can swallow climbers without warning.

Common Causes of Death

The primary causes of death on Everest include:

- Avalanches: One of the most significant threats, avalanches have caused numerous fatalities. The 2014 avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall killed 16 Nepali guides, marking one of the deadliest days in Everest history.

- Falls: The steep, icy, and often unstable terrain can lead to fatal falls. This risk is particularly high in areas like the Khumbu Icefall and near the summit.

- Altitude Sickness: Also known as Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), altitude sickness can cause fatal conditions as a result from the low oxygen levels at high altitudes.

- Exhaustion and Exposure: The extreme cold and physical demands of climbing Everest can lead to exhaustion and hypothermia. Climbers who are unable to descend quickly enough after summiting can succumb to these conditions.

The Death Zone on Mount Everest

The “death zone” on Mount Everest refers to altitudes above 26,247 feet (8,000 meters), where the oxygen levels are insufficient to sustain human life for an extended period. In this environment, the body cannot acclimate, leading to rapid deterioration of physical and mental capabilities.

Climbers face severe risks, including high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), which can be fatal without immediate descent. The death zone’s harsh conditions – freezing temperatures, unpredictable weather, and steep, icy terrain – further compound these risks. Prolonged exposure can lead to exhaustion, impaired judgment, and increased vulnerability to falls and other accidents.

What happens to the human body in the death zone? Find out here.

The Limits of Supplemental Oxygen

While supplemental oxygen helps mitigate some of the effects of climbing in the death zone, it does not eliminate all the risks. Supplemental oxygen increases the amount of oxygen available to climbers, but it cannot provide the same level of atmospheric pressure found at lower elevations. This means that climbers are still exposed to the physiological stresses of high altitude, such as reduced air pressure, which affects how oxygen is absorbed and utilized by the body.

Secondly, altitude sickness, including conditions like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), involves physiological responses to low oxygen environments. These conditions are caused by factors like fluid accumulation in the lungs and brain, which supplemental oxygen alone cannot always prevent. The underlying mechanisms, such as increased capillary pressure and leakage, are not fully addressed by simply increasing the available oxygen.

Recent Trends in Everest Deaths

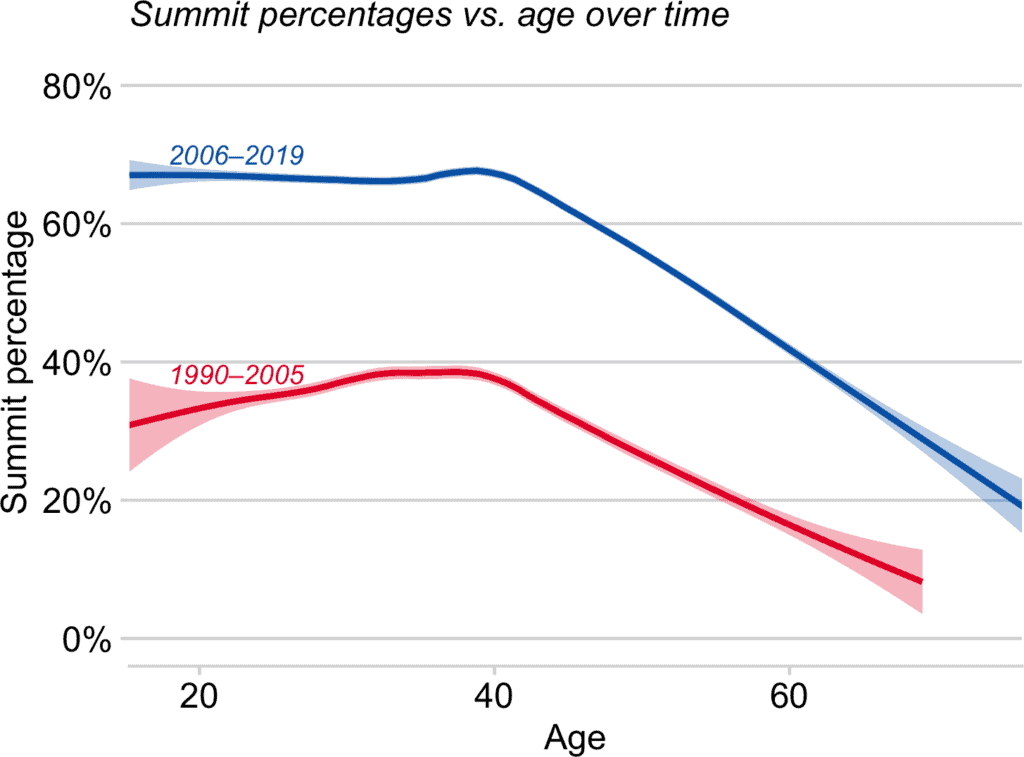

A 2020 study on the factors influencing success and mortality rates on Everest offers a clearer picture of the mountain’s dangers and the evolving trends over the years. The study titled “Mountaineers on Mount Everest: Effects of age, sex, experience, and crowding on rates of success and death” used data from the Himalayan Database, covering climbers’ attempts on Everest from 1990 to 2019.

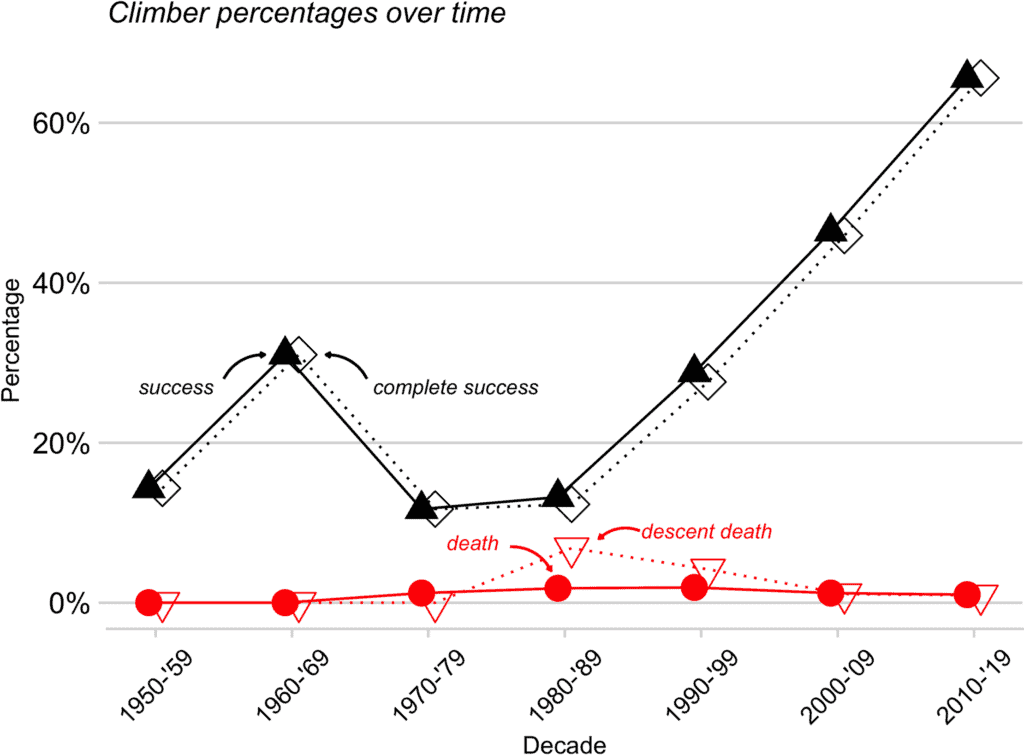

1. Success Rates Have Doubled

Currently, two out of every three climbers succeed on Everest. The study reveals that summit success rates have significantly improved over the past two decades. From 1990 to 2005, 32.8% of climbers reached the summit. This figure doubled between 2006 and 2019, with 66.5% achieving the summit. The reasons behind the improvement include better weather forecasting, presence of fixed ropes on much of the route, accumulated logistic and route experience, improved oxygen equipment, and shifts in oxygen use.

2. Death Rates Have Declined

The current overall death rate on Everest is 1% (2006–2019), showing a slight improvement from previous years. The death rate was 1.6% from 1990 to 2005.

Most deaths on Everest occur high on the mountain, particularly during descent. For recent climbers, 61.7% of all deaths occurred after summiting. Overall death rates are similar for men and women and are independent of experience.

3. Success Rate is Equal Among Men and Women

Gender differences do not seem to affect success rates on Everest. The study shows that women had a slightly higher success rate (68.2%) compared to men (64.4%) between 2006 and 2019. However, the statistical difference is not significant, indicating that gender does not drastically affect outcomes on Everest.

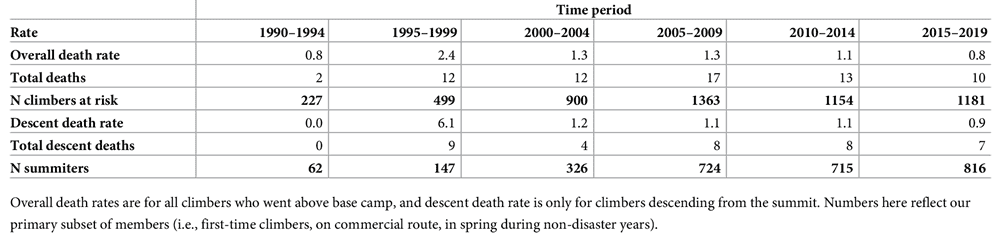

4. Success Rates Decline After Age 40

Age plays a critical role in climbing success and survival. The success rate declines steeply after age 40, dropping by 1.1% per year. Climbers over 59 are significantly less successful and face a higher death rate (4.1%) compared to younger climbers (0.9%). Older climbers may have relatively lower success rates for physical reasons or for behavioral ones, such as being more risk averse.

5. High Altitude Experience Less Important

Experience at high altitudes historically predicted higher success rates. From 1990 to 2005, climbers with prior high-altitude experience had a 40.9% success rate, compared to 28.1% for novices. Between 2006 and 2019, experienced climbers had a success rate of 67.6%, slightly higher than the 61.5% for less experienced climbers. However, the overall increase in success rates suggests that advances in commercial climbing practices may reduce the relative importance of prior high-altitude experience.

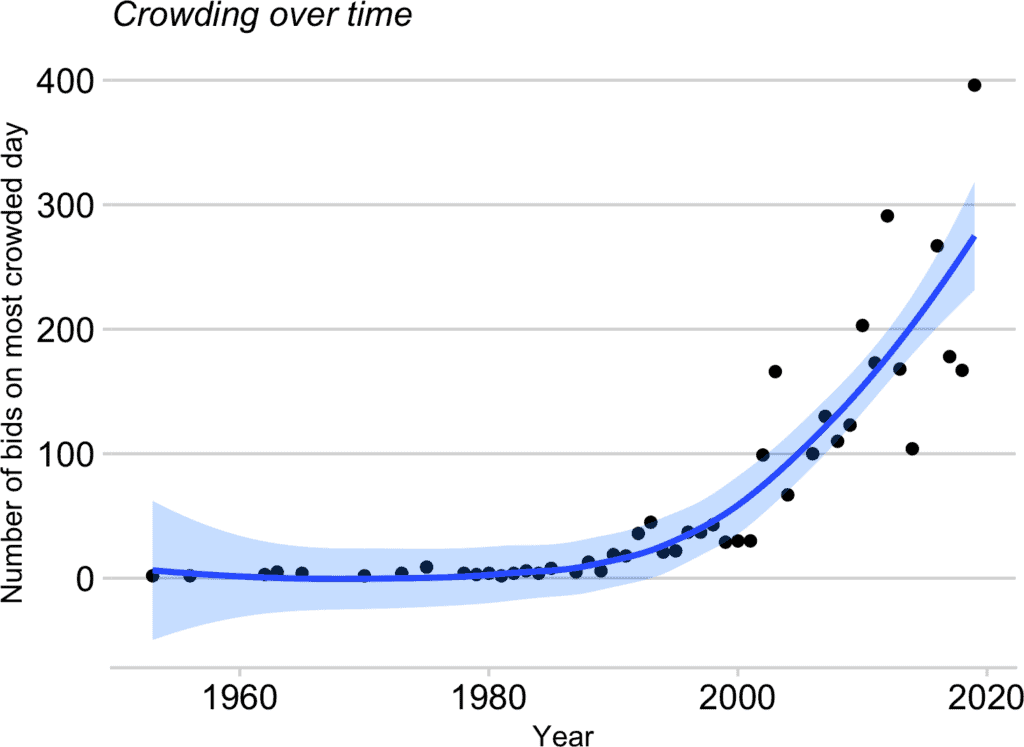

6. Overcrowding Did Not Impact Success or Deaths

In recent years, overcrowding has become a significant issue on Everest. Photos of long queues near the summit, especially on the Hillary Step, have highlighted the dangers of too many climbers attempting to summit simultaneously. Overcrowding can lead to bottlenecks, increasing the time climbers spend in the “death zone” above 26,247 feet (8,000 meters), where oxygen levels are critically low. This prolonged exposure can heighten the risks of altitude sickness and exhaustion.

However the data indicates that overcrowding has not significantly impacted success or death rates. In 2019, 65.9% of summit attempts were made on two peak days, yet success and death rates on these days were comparable to less crowded days. Improved weather forecasting encourages climbers to choose the safest days, mitigating the risks posed by crowding.

7. South Side Has Higher Success Than North Side

Climbers attempting Everest from the south side (Nepal) have a higher success rate (65.8%) compared to the north side (Tibet) at 58.4%. This can be attributed to the north side’s more technical terrain, making it inherently more challenging. Additionally, the north side is drier, colder, and windier, contributing to its increased difficulty.

Conclusion

Despite advancements in equipment, weather forecasting, and the support of experienced guides and Sherpas, the inherent dangers of climbing Everest continue to pose risks. While summit success rates have improved, with more climbers reaching the peak than ever before, the death rate remains high, particularly for older climbers and those attempting the north route. The statistics also reveal that factors such as age and prior high-altitude experience effect success and survival rates.