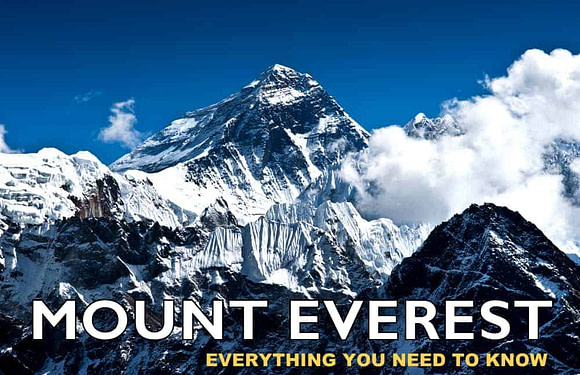

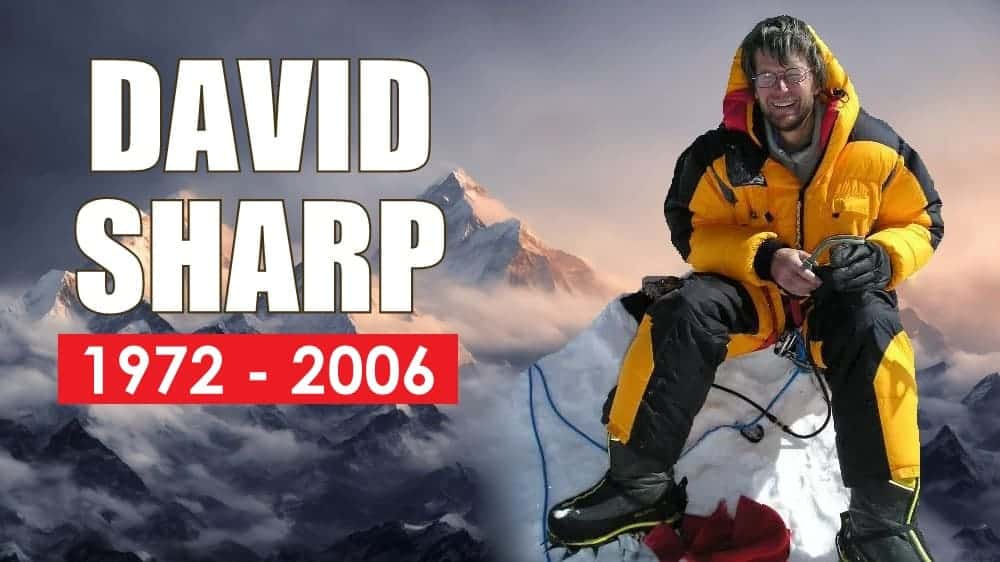

David Sharp’s journey on Mount Everest is a controversial chapter in the annals of mountaineering. As he lay dying near the top of Everest in 2006, numerous climbers failed to help him. Instead, they walked past him on their way to and from the summit, resulting in Sharp’s demise on the mountain. The episode raised questions about ambition, camaraderie, and the unwritten codes of the mountaineering community.

WARNING: This article contains graphic images. Reader discretion is advised.

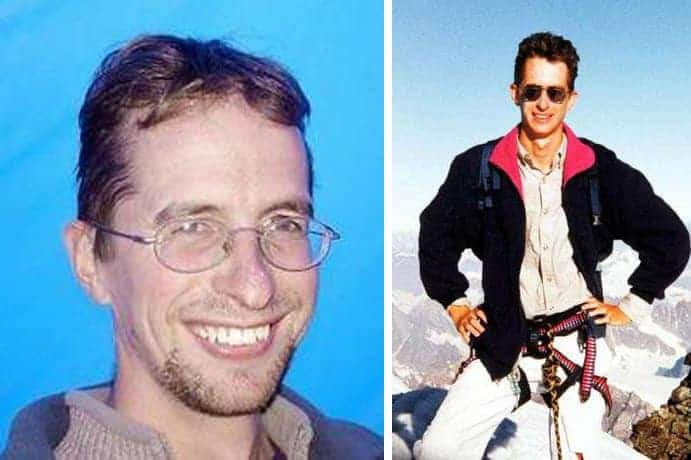

Sharp’s Early Life

David Sharp was born into a world far removed from the icy reaches of the world’s highest peaks. Growing up in Hertfordshire, England, his early life seemed to follow a conventional path. After completing his education at the University of Nottingham, where he attained a Masters in Engineering, Sharp started a promising career with a defense contractor. Yet, beneath this veneer of normalcy beat the heart of an adventurer.

Sharp’s foray into mountaineering began with the climbs of lesser-known peaks. Then, he gradually escalating to climbing major peaks, such as the Matterhorn in the Swiss Alps, and some of the tallest mountains in Europe and Africa, including Elbrus and Kilimanjaro. This passion for the mountains would eventually steer him towards the Himalayas and, ultimately, Everest.

His Philosophy: No Supplemental Oxygen

It is standard to use supplemental oxygen on Mount Everest and other extremely high peaks to mitigate the risks of low oxygen atmospheres. As climbers continue to ascend, the air becomes so thin that the amount of oxygen available is insufficient to sustain normal bodily functions. Supplemental oxygen helps prevent hypoxia, a condition where the body or a region of the body is deprived of adequate oxygen supply.

David Sharp was a purist when it came to mountaineering. He valued climbing in its most traditional and elemental form. Sharp believed that reaching the summit without artificial aid as a more genuine accomplishment, testing the limits of human endurance and adaptation to extreme environments.

Moreover, Sharp’s belief in climbing without supplemental oxygen likely reflected his desire for self-reliance. His 2002 ascent of Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth-highest peak, without oxygen, reinforced his confidence in his body’s ability to adapt to high altitudes. The expedition leader noted that Sharp was “definitely the strongest member of our team.”

This approach, while admirable for its commitment to the ethos of mountaineering, carries significant risks. The “death zone” above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) on Everest is notoriously dangerous, with oxygen levels so low that human life cannot be sustained for long periods. Without supplemental oxygen, climbers are more susceptible to altitude sickness, frostbite, hypoxia, and other life-threatening conditions.

2003 & 2004 Everest Expeditions

Sharp’s first Everest expedition occurred in 2003, within a team led by a fellow British climber. During the ascent, he developed frostbite, leading him to turn around below the Second Step, just 650 vertical feet (200 meters) from the summit. He eventually lost some of his toes to frostbite, which he blamed on using cheap boots. Despite not reaching the summit himself, Sharp was seen as an exceptionally strong and well-acclimatized mountaineer.

In 2004, Sharp joined a European team and this time he ventured high into the mountain’s death zone. It was reported that he and the expedition leader were at odds due to Sharp’s preference for solo climbing and his reluctance to use oxygen. Again, Sharp failed to make it to the summit, located at 29,032 feet (8,849 meters). But, he was close; he managed to reach 28,000 feet (8,500 meters).

This expedition reinforced his desire to climb Everest without guides or supplemental oxygen.

Sharp’s Last Everest Climb

In 2006, Sharp decided to make a solo attempt on Mount Everest. “If I don’t do it this time, I’m not coming back,” Sharp told others. He was going to start his teaching career later in the year.

He arranged his climb through Nepal-based agency Asia Trekking, opting for their “basic service” package. This choice provided him with a permit, logistical support up to Advanced Base Camp, and a limited supply of oxygen.

The booking with Asian Trekking cost about $6,200, which was considerably lower than the $40,000 or so that top Western companies charged. Sharp’s decision not to join a full-service expedition team was motivated by both financial considerations and a desire for autonomy. By late April, he was at Everest Base Camp, acclimatising and preparing for his summit bid.

Sharp began his final summit attempt on the North Col from one of the higher camps late on May 13, 2006. The details surrounding his final hours remain unclear. Given the solitary nature of his climb and his decision not to carry a radio or satellite phone, direct observations of his progress are sparse. There is no definitive record of him reaching the summit. However, some climbers believed they saw someone fitting Sharp’s description near the summit area, and some speculated that he might have reached or nearly reached the summit before encountering difficulties on his descent.

The Descent and Final Hours

On May 14, 2006, as Sharp descended, he sought refuge in Green Boots Cave. This overhang near the summit trail was named after the presence of a frozen body, Tsewang Paljor, who died here in 1996. Conditions at this altitude are extreme, with temperatures well below freezing and oxygen levels less than a third of those at sea level.

Climbers reported seeing Sharp huddled in the cave, wearing his top of the line Millet mountaineering boots. Some thought he was resting or already deceased.

A team of Turkish climbers passed Sharp in the early hours of May 15. They observed him alive but in a dire state, suffering from severe frostbite and oxygen depletion. Efforts to assist were minimal, constrained by their own oxygen supplies and the harsh conditions.

Members of a commercial expedition led by Russell Brice, including double amputee climber Mark Inglis, encountered Sharp. They noted his perilous condition but felt unable to render effective aid due to his critical state and their expedition’s priorities. Two climbers noted that Sharp was “too far gone to really be able to do anything”.

Sharp’s last words to a Sherpa who had tried to help him were, “My name is David Sharp. I’m with Asian Trekking, and I just want to sleep.” In time, Sharp succumbed to the harsh conditions and died on the mountain. He was 34 years old.

Is David Sharp Still on Everest?

Yes. David Sharp’s body is still on Mount Everest, though he was relocated from Green Boots Cave.

After his death, his body remained in high on the northeast ridge for about a year. Sherpas took Sharp’s body to a nearby cliff edge and respectfully pushed it over the side of the North Face. He joins the 200+ frozen bodies on Mount Everest.

Aftermath and Controversy

In the wake of Sharp’s death, the mountaineering community has been forced to confront difficult questions. Sharp’s predicament and the decision of many climbers to proceed without offering substantive assistance sparked a global controversy. The incident raised questions about the ethics of climbing, the responsibility climbers have towards one another, and the priorities of commercial expeditions.

Certainly, Sharp himself should be held accountable for his death. There are obvious, inherent risks of climbing Everest, especially without the support of a full expedition team and with minimal oxygen. These were critical factors in the tragedy.

While some climbers attempted to assist Sharp, their efforts were hampered by the extreme conditions and the limitations of their own expeditions. The majority passed by, driven by the relentless pursuit of the summit.

Sharp spoke to his mother before he left for Everest for the last time. He reassured his mom not to worry about him, because “you are never on your own. There are climbers everywhere.”

Approximately 40 climbers witnessed Sharp’s demise.

May he rest in peace.