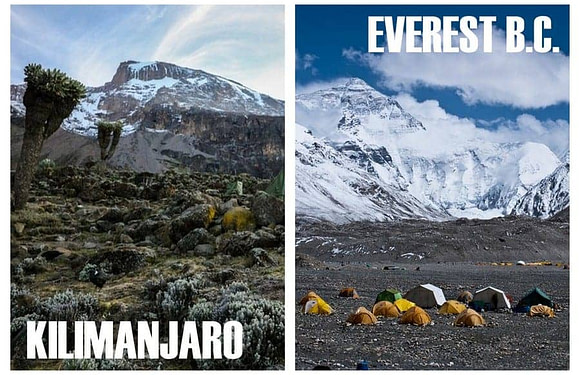

Mount Everest, the highest mountain in the world, is the crown jewel for mountaineers. Rising 29,032 feet (8,849 meters) tall, the peak is known for its danger. In the spring of 1996, the quest to climb Mount Everest resulted in one of the deadliest tragedies in Everest’s history. The events that unfolded during that climbing season raised critical questions about the commercialization of high-altitude mountaineering and the limits of human determination.

Commercialization of Everest Expeditions

By the 1990s, climbing Mount Everest had evolved from an elite pursuit into a commercial enterprise. Guided expeditions began offering packages that made the summit accessible to less experienced climbers willing to pay the substantial fees. This shift brought increased traffic to the mountain, as well as concerns about overcrowding, environmental impact, and the preparedness of climbers who might lack the necessary high-altitude experience.

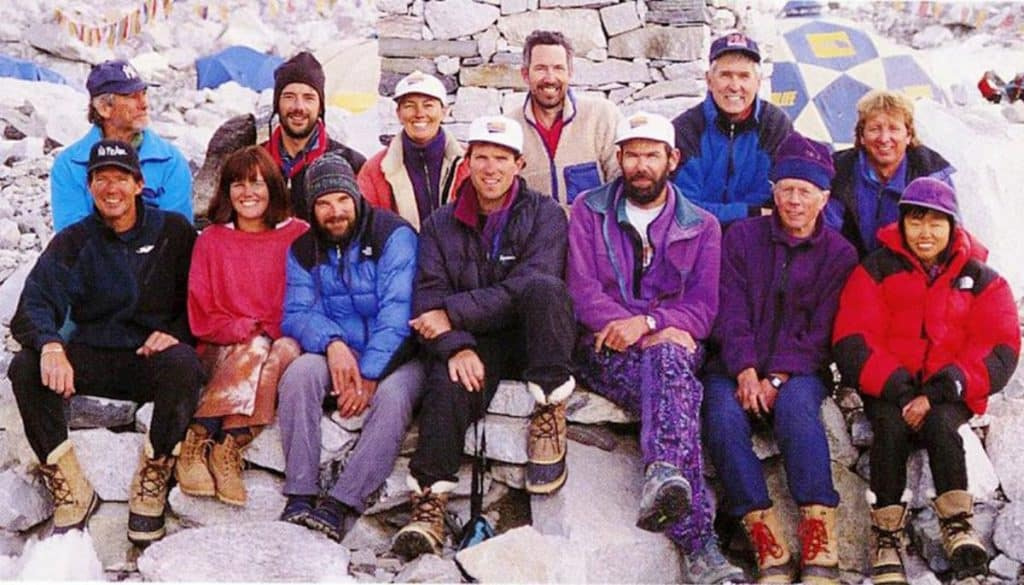

These commercial expeditions were central to the 1996 tragedy:

- Adventure Consultants, led by Rob Hall from New Zealand.

- Mountain Madness, headed by American climber Scott Fischer.

- Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), attempting to summit Everest via the Northeast Ridge route from the Tibetan side.

- Taiwanese National Expedition, led by Makalu Gau.

- South African Everest Expedition, led by Ian Woodall.

Events Leading Up to the Disaster

Mount Everest, the highest peak in the world at 29,032 feet (8,849 meters), requires climbers to ascend in stages to acclimatize to the thin air and harsh conditions. The journey to the summit involves a series of camps, each serving as a critical waypoint for rest, acclimatization, and preparation.

Here are the camps on Mount Everest:

- Base Camp (5,364 meters / 17,598 feet)

- Camp I (6,065 meters / 19,900 feet)

- Camp II (6,400 meters / 21,000 feet)

- Camp III (7,200 meters / 23,600 feet)

- Camp IV (7,920 meters / 26,000 feet)

- Summit (8,849 meters / 29,032 feet)

The climbing season typically spans from April to May, offering climbers the best chance to reach the summit before the monsoon arrives. In 1996, an unusually high number of climbers converged on Everest, all aiming for the summit during the narrow window of favorable weather.

Climbers arrived at Base Camp in April, beginning the critical process of acclimatization. This involved ascending to higher camps and returning to lower elevations to allow their bodies to adjust to the thinning air. Both Adventure Consultants and Mountain Madness followed similar schedules, establishing a series of camps along the Southeast Ridge route.

The teams planned their summit attempts for May 10, 1996, targeting a forecasted window of good weather. Despite the potential benefits of collaboration, there was limited coordination between the different expeditions. Concerns arose about the number of climbers attempting the summit simultaneously, which could lead to bottlenecks at critical points and delays that might prove dangerous.

2:00 Turnaround Time Ignored

Climbers departed from Camp IV on the South Col shortly before midnight on May 9, embarking on the final push to the summit. Initially, the ascent proceeded smoothly under clear skies. Spirits were high as climbers made their way toward landmarks such as the Balcony and the South Summit, motivated by the prospect of achieving their goal.

As the ascent continued, several issues emerged. Bottlenecks developed at critical points like the Hillary Step, a narrow and steep section near the summit. Delays were exacerbated by the absence of fixed ropes that were supposed to be installed in advance. Guides and Sherpas had to set up these ropes on the spot, causing significant time losses. Additionally, many climbers disregarded the predetermined turnaround time of 2:00 PM, a safety protocol intended to ensure they could descend before nightfall and worsening weather.

The decision to push past the turnaround time was influenced by various factors. Climbers faced immense pressure to reach the summit after investing considerable time, effort, and money. Guides grappled with balancing client expectations and safety concerns. The desire to achieve the summit overshadowed safety precautions, setting the stage for disaster.

On May 10, 1996, several climbers from different expeditions reached the summit of Mount Everest in the late afternoon. This delay proved fatal as it left insufficient time for a safe descent before the onset of a severe storm.

The Onset of the Storm

In the late afternoon, a sudden and severe storm enveloped the mountain. High winds and heavy snowfall drastically reduced visibility and temperature, transforming the environment into a perilous maze. Climbers found themselves in whiteout conditions, struggling to locate fixed ropes and the route back to Camp IV.

The storm’s ferocity led to disorientation among the climbers. Physical exhaustion from the ascent, combined with the effects of high altitude, impaired their judgment and ability to navigate. Groups became separated, and communication broke down as radio batteries failed in the extreme cold. The harsh conditions amplified the dangers inherent in high-altitude climbing.

Efforts to coordinate rescues and provide assistance were hampered by malfunctioning equipment and the inability to establish clear communication between climbers and Base Camp. Misunderstandings about the locations and statuses of team members hindered effective response efforts, leaving many climbers vulnerable to the elements.

The Tragic Outcomes

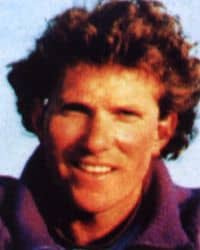

Rob Hall and his client Doug Hansen were among the first to reach the summit around 2:45 PM. Their ascent was marked by exhaustion, and Hansen began to deteriorate shortly after reaching the top. Despite Hall’s efforts to assist him, the extreme conditions impeded their descent. Hall refused to leave Hansen, ultimately leading to both of their tragic deaths.

Andy Harris, a guide with Adventure Consultants, was instrumental in supporting the team’s clients. On the descent, Harris became disoriented, possibly due to hypoxia affecting his cognitive functions. He mistakenly believed he had found full oxygen bottles at the South Summit when they were empty, indicating his impaired judgment. Harris was last seen by other climbers heading back up the mountain, attempting to assist Hall and Hansen. In the chaos of the storm, he vanished, and it is presumed that he fell from the ridge or succumbed to the elements. His body was never recovered.

Yasuko Namba, a seasoned Japanese climber with Adventure Consultants, summited around 3:30 PM. Shortly after reaching the peak, she began to experience severe fatigue and symptoms of altitude sickness. As night fell and the storm raged, Namba, along with Beck Weathers, collapsed on the South Col near Camp IV. Rescuers initially attempted to help them but, assessing their critical condition and the danger to themselves, they made the agonizing decision to leave Namba, believing she could not be saved. Weathers miraculously survived despite severe injuries.

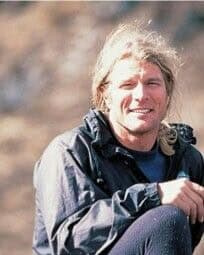

Scott Fischer, leading the Mountain Madness expedition, reached the summit approximately 3:45 PM. During the ascent, Fischer exhibited signs of fatigue and possible illness, potentially exacerbated by a recent bout of gastrointestinal issues and lack of sleep. On the descent, Fischer’s condition deteriorated rapidly. Disoriented and physically weakened, he was unable to navigate or continue unaided. Anatoli Boukreev, a guide on his team, found Fischer and attempted to assist him, but Fischer insisted that Boukreev save himself and help others. Fischer was left in a sheltered spot near the route, but he did not survive the night. Boukreev rescued several climbers.

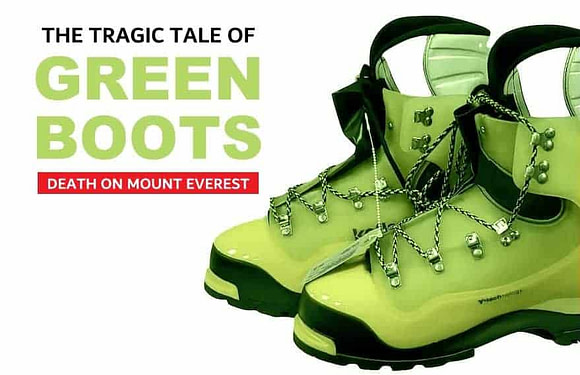

The Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) team, consisting of Subedar Tsewang Samanla, Tsewang Paljor, and Dorje Morup, reached the summit around 4:00 PM via the Northeast Ridge. Their late arrival left them vulnerable to the rapidly deteriorating weather conditions. Disoriented and exhausted, they struggled to find their way back to the high camp. Samanla became separated from other team members. His body was never found, but it is believed that he died somewhere along the Northeast Ridge. Paljor sought shelter in a small limestone cave and died there, becoming a permanent marker on the mountain known as “Green Boots.” Morup initially turned back but later decided to continue upward, driven by a desire to support his teammates. On the descent, he became stranded alone in the storm. He managed to radio Base Camp, reporting his critical condition and pleading for help. Despite efforts to guide him back remotely, he succumbed to the conditions. Some believe that “Green Boots” is actually the body of Morup.

Chen Yu-Nan, a climber with the Taiwanese expedition, died on May 9, a day before the main disaster unfolded. While descending through the Khumbu Icefall, Chen slipped and fell into a crevasse.

In summary, most of the climbers involved in the 1996 Everest disaster reached the summit between 2:45 PM and 4:00 PM, well past the recommended turnaround time. This critical timing mismatch, combined with the sudden and severe storm, created a lethal environment that overwhelmed even the most experienced mountaineers, resulting in one of the most tragic chapters in Everest’s climbing history.

Media Coverage

The disaster attracted global media attention, bringing widespread scrutiny to the practices of commercial guiding on Everest.

The events inspired several personal accounts that provided differing perspectives on what transpired. Journalist and climber Jon Krakauer published “Into Thin Air,” offering a detailed narrative of the disaster and raising questions about decision-making and responsibility. Boukreev co-authored “The Climb,” defending his actions and providing an alternative viewpoint.

In the wake of the disaster, the mountaineering community undertook a critical examination of practices on Everest. Emphasis was placed on adhering strictly to safety protocols, such as turnaround times. Expedition companies reevaluated their approaches to client screening, guide responsibilities, and resource allocation. There was a heightened focus on the ethical considerations of guiding inexperienced climbers in such a dangerous environment.

While the tragedy prompted calls for stricter regulations and greater emphasis on safety, the commercialization of Everest continued. The number of climbers attempting the summit has increased in subsequent years, leading to ongoing concerns about overcrowding and environmental degradation.