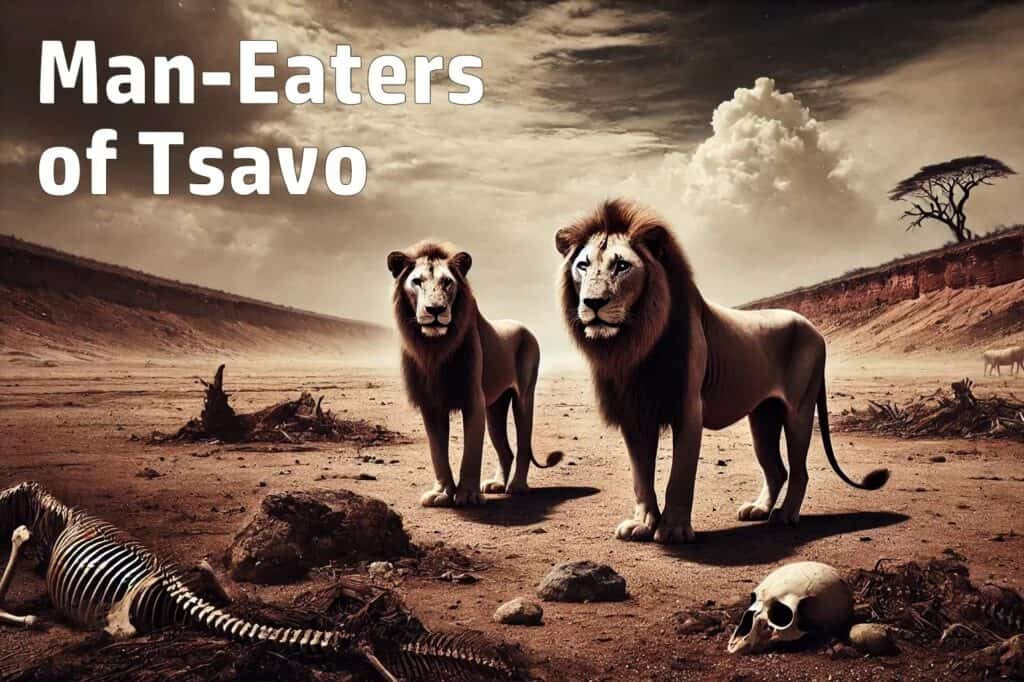

The Man-Eaters of Tsavo are perhaps the world’s most notorious wild lions, having reputedly killed dozens of railway workers on the Uganda Railway project in 1898. Their story is a tale of survival and terror in the complex interaction between human development and wildlife behavior.

The Uganda Railway Project

The Uganda Railway was one of the most ambitious engineering projects of its time. Planned by the British colonial administration, the railway connected the East African interior with the coast. Despite its name, most of the railway was in Kenya, with only its final segments reaching Uganda. The line stretched over 580 miles (930 km) from the port of Mombasa to Kisumu, a key port city on Lake Victoria. Before the railway, transportation for goods and passengers relied heavily on caravans, which were slow and inefficient.

The construction of the railway began in 1896 and faced numerous difficulties. The terrain was incredibly varied, with the line passing through forests, across plains, and over escarpments. Workers had to build bridges over wide rivers and deep gorges.

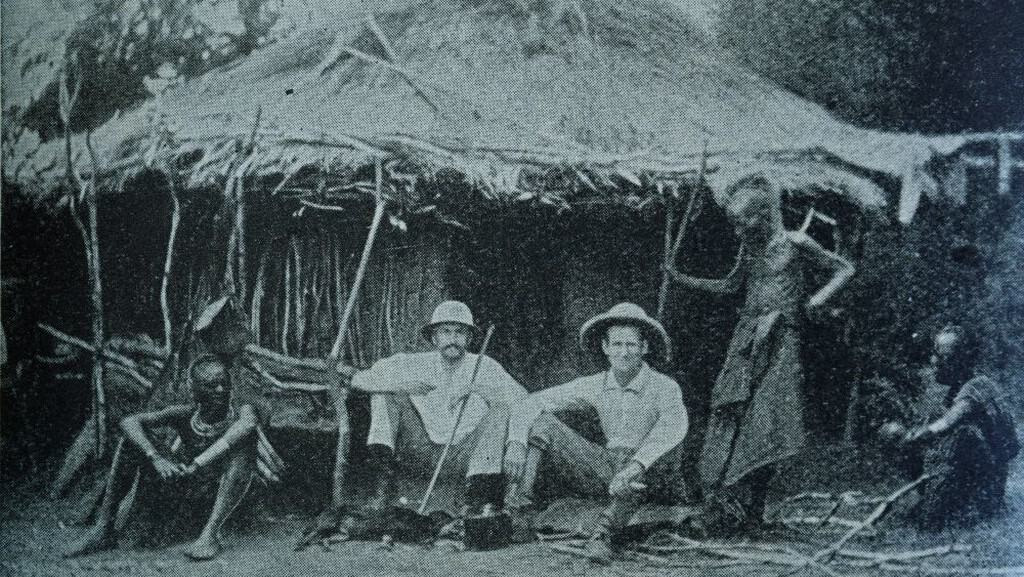

Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson was brought in by the British government to supervise the building of the Tsavo River bridge. This massive 984-foot (300 m) long bridge over the Tsavo River was a vital part of the railway’s progress.

The Tsavo Lions’ Attacks on Workers

Workers, primarily brought in from British India, lived in rudimentary camps along various points of the railway. In March 1898, as workers began building the Tsavo River bridge, two lions began attacking the camps. These lions, unusually bold and aggressive, didn’t follow typical lion behavior. Instead of hunting at night and targeting livestock, they dragged workers from their tents, often during daylight, and devoured them.

For months, fear gripped the workforce. Workers tried various tactics to protect themselves, including setting up thorn barriers around their tents and lighting large fires at night. But the lions continued to strike. The animals appeared to defy every attempt to drive them away, and work on the railway slowed to a crawl as workers either fled or refused to continue.

The lions, which lacked manes, were male and larger than most other lions in the region. Their aggressive behavior puzzled many, as attacks by lions is typically rare and usually occurs when lions are either old or injured. In this case, both lions appeared healthy. In about nine months, the man-eaters of Tsavo killed an estimated 35 to 135 men. The exact number is still debated today, but the psychological toll was undeniable.

Their Reign of Terror Ends

To stop the attacks, Lieutenant Colonel Patterson took it upon himself to kill the man-eating lions.

Patterson’s approach to hunting the lions was methodical, patient, and relentless, given the high stakes. He initially set traps to capture the lions, using animal carcasses or human remains as bait, but these methods failed. The lions, already proven to be unusually cunning, avoided the traps. Patterson realized he would need to adopt more direct tactics.

He began staking out bait—either freshly killed livestock or, in some cases, live goats—near the camps where the lions had previously attacked. Patterson would then build platforms, sometimes in trees, where he would sit and wait, rifle in hand, through the night.

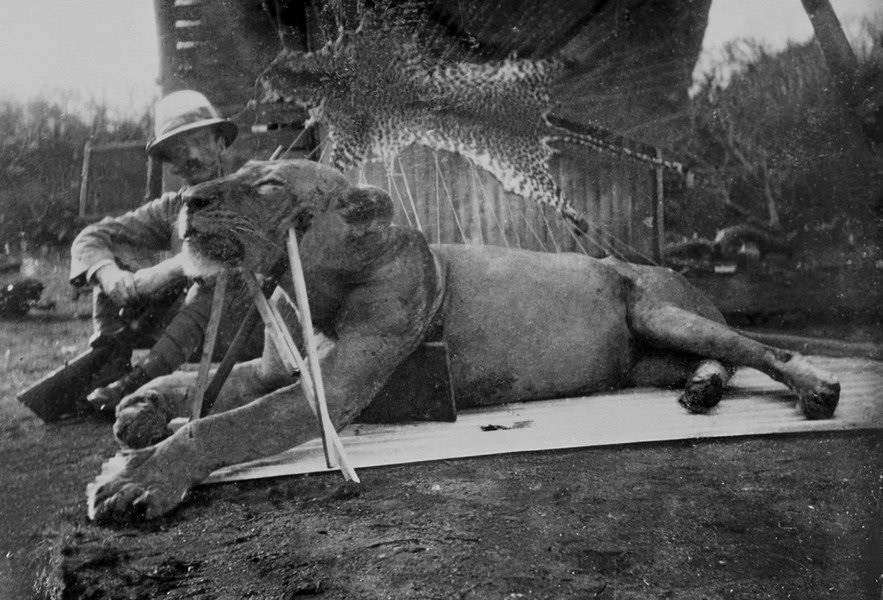

Patterson’s perseverance paid off after several close encounters. On the night of December 9, 1898, after hours of waiting, he saw one lion approach his bait. He fired, wounding the lion, but it ran into the bush. Patterson tracked the injured animal the next morning, eventually finding and killing it.

Three weeks later, on December 29, 1898, the second lion was taken down in a similar fashion, although this one proved to be more difficult to kill. Patterson shot it multiple times over the course of several nights. After tracking it down, he delivered a fatal shot, ending its reign of terror.

Both lions were enormous, measuring nearly 9 feet (2.7 meters) in length.

Once the lions were gone, work on the railway resumed. The Tsavo bridge was completed in February 1899, and construction continued westward.

Why Didn’t the Tsavo Lions Have Manes?

First, it’s important to understand that not all male lions grow manes. Tsavo lions belong to a distinct population with different genetic traits from lions in other parts of Africa. Maneless or partially maned males are more common in this region, suggesting that it’s a natural variation within the local lion population.

Additionally, the Tsavo region is extremely hot, with temperatures regularly exceeding 100°F (38°C). In such a climate, having a large mane could be a disadvantage. Manes are known to trap heat, and in the extreme heat of Tsavo, this could make it harder for lions to cool down. The lack of manes in this population may be an adaptation to hot environmental conditions.

Some researchers also suggest that the maneless trait may be linked to the lions’ role as solitary hunters. Unlike most lions, which rely on pride dynamics and hunt in groups, the Tsavo lions were known to hunt alone or in pairs. A large mane, which is often used as a signal of dominance and mating strength, might not be necessary in a region where lions are more independent and hunting stealth is more critical than social status.

Why Did the Lions Prey on Humans?

The reasons behind the Tsavo lions’ behavior have been the subject of much speculation and scientific study. Several theories have been proposed:

Examinations of the skulls and dental remains of the lions revealed significant dental ailments. One lion had a severe dental abscess that may have made hunting typical prey painful, potentially prompting it to hunt humans, which would have been easier targets.

Some historians suggest that a concurrent outbreak of rinderpest disease may have severely reduced the numbers of natural prey around Tsavo, pushing the lions to seek alternative food sources.

Lastly, one theory suggests that the lions may have developed a taste for human flesh from scavenging human corpses, a practice that could have begun during slave trade caravans passing through the region.

What Happened to the Tsavo Lions?

After Patterson killed the lions, he had their skins and skulls preserved. Initially, Patterson used them as floor rugs in his home. In 1924, he sold the remains to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago for $5,000, a significant sum at the time.

Once in Chicago, the lions were mounted as full-body taxidermy specimens, but their appearance changed slightly. Since the skins had been used as rugs for years, they had worn down and were stretched during the mounting process, making the lions appear smaller and leaner than they actually were in life.

The lions are on permanent display in the museum to this day, housed in a dedicated exhibit. They are a popular attraction, drawing visitors intrigued by their gruesome history.

Some Kenyans feel that the lions, which are a part of their natural and colonial history, should be repatriated and displayed in Kenya. There have been periodic calls for the lions to be returned. These sentiments are part of a broader conversation on returning cultural and historical artifacts to their countries of origin. However, the Field Museum has not indicated any intention of returning the lions.

The Ghost and the Darkness Film Adaptation

After his experience with the lions of Tsavo, Patterson wrote a book titled The Man-Eaters of Tsavo. Published in 1907, the book details the construction of the Uganda Railway, the lion attacks, and Patterson’s hunt to stop them. It became an instant success due to its thrilling narrative and Patterson’s firsthand account of the terror that gripped the railway camps.

Hollywood adapted Patterson’s story into the 1996 film The Ghost and the Darkness. Starring Val Kilmer as Patterson and Michael Douglas as a fictional character named Charles Remington, the film dramatizes the events surrounding the lion attacks. While it stays largely true to the core of Patterson’s account, the movie introduces some fictional elements for the sake of suspense and action.

Though the film took creative liberties, it brought widespread attention to the historical events of Tsavo and introduced the story to a new generation.