Africa is the warmest continent on Earth.

When people envision African weather, several common stereotypes come to mind. Many people associate the continent with the vast, sun-scorched landscapes of the Sahara Desert. Or perhaps they imagine dense, humid rainforests of Africa’s equatorial regions. Of course, there is the iconic image of Africa’s savanna—a mix of grassland and scattered trees.

Snowy environments are often the last thing that comes to mind. However, it does snow in Africa, even though it’s rare. Snow primarily falls in mountainous regions and high-altitude areas where the temperatures drop sufficiently.

Africa’s Weather Patterns

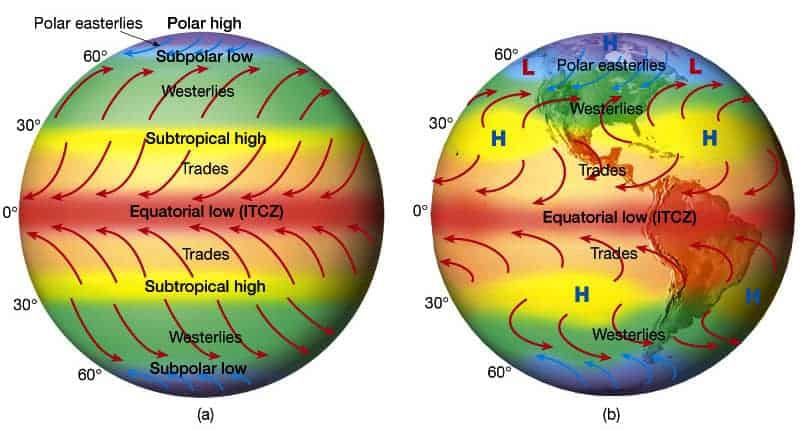

Africa’s location across the equator means it has both northern and southern hemispheres, creating complex weather systems influenced by both global and regional factors. The continent lies within the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a belt of low pressure that encircles the Earth near the equator. This zone influences Africa’s weather patterns significantly.

In equatorial regions, such as the Congo Basin and parts of West and East Africa, the climate is typically tropical, with high temperatures and humidity year-round. These areas receive consistent rainfall, often exceeding 80 inches (2,000 mm) annually, supporting lush rainforests.

Moving away from the equator, the tropical savanna climate emerges, characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. Countries like Tanzania and Kenya experience high temperatures throughout the year, with the wet season bringing essential rainfall that supports both agriculture and wildlife.

In contrast, the desert regions, particularly the Sahara in North Africa and the Namib and Kalahari deserts in Southern Africa, are defined by extreme heat during the day and cooler nights. Rainfall is scarce, and the landscape is dominated by vast stretches of sand and sparse vegetation.

The Mediterranean climate in the far northern and southern tips of the continent, including parts of Morocco, Algeria, and South Africa, features warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters.

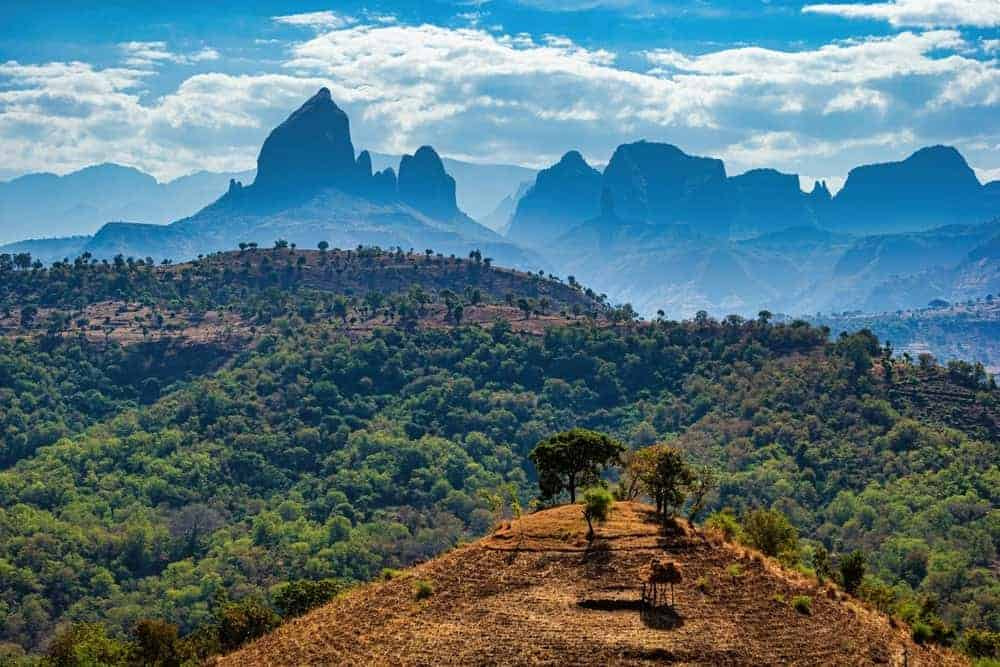

Mountainous regions like the Ethiopian Highlands, the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, and Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania experience cooler temperatures due to higher altitudes. These areas can receive significant rainfall, and at the highest elevations, snow and ice are present year-round, a surprising feature in an otherwise warm continent.

What Creates Snow?

In order for snow to form, specific atmospheric conditions must be met.

The air temperature must be at or below 32°F (0°C). Adequate moisture is required. When warm air rises and cools, the water vapor within it condenses into tiny ice crystals. These crystals clump together to form snowflakes around tiny particles called ice nuclei, which could be dust, pollen, or other small particulates in the atmosphere. Finally, a stable atmospheric environment is necessary to allow snowflakes to grow and fall without melting.

Where Does it Snow in Africa?

Here are some areas that regularly receive snow in Africa.

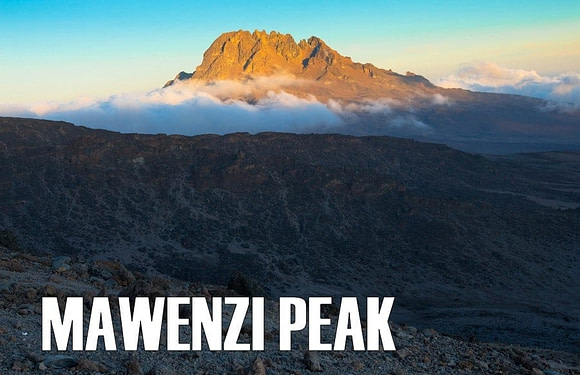

Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania:

Perhaps the most famous snow-capped peak in Africa, Mount Kilimanjaro stands at 19,341 feet (5,895 meters). Snow is present year-round on its summit, thanks to its high altitude. The glaciers and ice fields that cap Kilimanjaro are remnants of a much larger ice mass that has been receding for over a century. However, due to global warming, these glaciers are shrinking and may disappear entirely within a few decades if current trends continue.

Mount Kenya, Kenya:

Mount Kenya, Africa’s second-highest peak, also has permanent snow and ice near its summit at 17,057 feet (5,199 meters). The mountain is located just south of the equator, yet its highest peaks are covered in snow.

The Atlas Mountains, Morocco:

Located in North Africa, the Atlas Mountains experience seasonal snow, particularly in the winter months. The highest peak, Mount Toubkal, stands at 13,671 feet (4,167 meters), and its summit is often snow-covered from November to April. The Atlas Mountains even offer some unique skiing opportunities.

The Rwenzori Mountains, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

The Rwenzori Mountains is another region in Africa where snow exists. Known as the “Mountains of the Moon,” the Rwenzoris are home to Africa’s third-highest peak, Mount Stanley, at 16,763 feet (5,109 metres). Snow and glaciers are present at the highest elevations year-round, though they have been receding due to climate change.

The Drakensberg Mountains, South Africa and Lesotho:

The Drakensberg range in South Africa and Lesotho also receives snow during the winter months. The highest peak, Thabana Ntlenyana, at 11,423 feet (3,482 meters), often sees snowfall from June to August. The Kingdom of Lesotho, landlocked within South Africa, has ski resorts that rely on this seasonal snow.

Climate Change and Its Impact on Mount Kilimanjaro

Climate change is an urgent global issue, and its effects are clearly visible in Africa, particularly in its high-altitude regions. Mount Kilimanjaro has become a symbol of the broader impacts of global warming.

Over the past century, Kilimanjaro’s glaciers have been retreating at an alarming rate. Scientists estimate that the mountain has lost over 80% of its ice cover since 1912. If the current trends continue, Kilimanjaro’s remaining glaciers and permanent snow may disappear entirely within the next few decades. The primary drivers of this phenomenon are rising global temperatures, changing weather patterns, and reduced precipitation in the region.

As temperatures increase, the delicate balance required to sustain snow and ice at high altitudes is disrupted. Warmer air can hold more moisture, which can lead to increased rainfall instead of snowfall at elevations that traditionally received snow. Furthermore, changes in wind patterns and cloud cover can affect the amount of moisture that reaches these high-altitude regions, further accelerating the melting process.

The loss of Kilimanjaro’s glaciers would have significant ecological, cultural, and economic impacts. These glaciers play a strong role in the mountain’s ecosystem. They regulate the flow of water to the surrounding areas, supporting agriculture, wildlife, and local communities. The disappearance of this ice would lead to water shortages and negatively impacting the livelihoods of those who depend on the mountain’s resources.